What should the next UK government do?

2. Devolving economic powers in England

Note: everything in this piece is a strictly personal view

The UK is divided by geography. This inequality, along with the dominance of London over public life, is an underrated political issue. It is now almost a cliché to say that the UK is one of Europe’s most centralised states, and also one of its most starkly divided in terms of living standards in different parts of the country. Geography is not the UK’s only dividing line – inequalities by income, age and race also loom large – but it matters, and it is often linked to other forms of inequality.

The UK’s geography is a political and economic problem wrapped up together. It seems to hold back progress in many parts of the country, it makes people angry, and it ultimately threatens the make-up of the UK. That perhaps explains why Boris Johnson backed up his Brexit message with a Levelling Up one in 2019, and it certainly explains Gordon Brown’s Constitutional Review for the Labour Party, published this week. Geographic inequality and the centralisation of power is an issue of constitutional – existential – importance for the UK. It will be one of the most important issues for the next government, and it is welcome that Labour are thinking so thoroughly about how to address it.

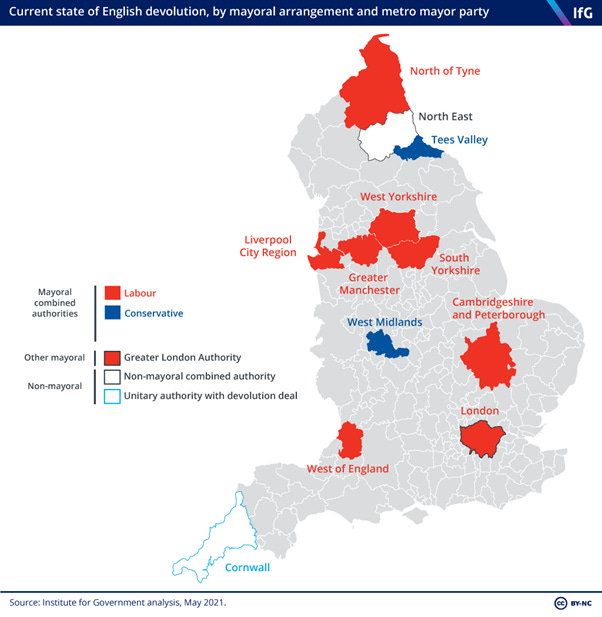

The Brown Review is an expansive piece of work, but I want to focus on one issue within it: the devolution of powers to local government in England. Partly because it’s what I know best – I was closely involved in City Deals and the creation of metro mayors from inside government – and partly because devolution in the UK’s other nations is more advanced, though imperfect. In devolution terms, England has been left behind, and the next government will need to help it catch up. But devolution is a very complex process, and not an especially glamorous one in practice, which means it doesn’t always get the political attention it deserves. So how should the next government do it?

Why devolve power?

There are two reasons to devolve power in England: a political one and an economic one.

The political case is straightforward. In a country that seems dominated by London, having local figureheads with real power to change local people’s lives is a powerful drug. Different parts of the country are different, so why not let them run themselves slightly differently? If things are going wrong where people live, it’s better if they can hold a local leader to account than direct their frustration towards a big government in London.

There are some mild drawbacks politically. Many people resent having additional tiers of government and more politicians, at least until they’ve seen them do something useful. And local governments are often run by a different party to the national government. But these issues are surmountable, as long as both central and local government are grown up enough to cope with not always agreeing with each other.

The economic case is more difficult to make. I’ll be honest: I don’t think there’s any clear-cut evidence that devolution is good or bad for economic growth. And I’m not sure there ever will be – there are just too many variables in local economic performance. But there are still good reasons to devolve that fall short of hard evidence. First, as many a local leader would tell me during my Whitehall days, the centralised status quo simply does not work. There really isn’t much to lose from trying devolution, at least on economic powers, because the current system works so badly for many places. Second, there is a persuasive case that devolution can improve how some services are delivered. If you doubt this, consider why London (which has long had devolved transport powers) is so far ahead of the rest of the country on transport. It doesn’t take much imagination to extrapolate this.

I can’t prove a conclusive link between decentralisation and economic growth, but I am pretty confident that having effective public services – particularly transport and housing – is an important factor in long term growth. We currently don’t have that in any part of England outside London, and devolution is one plausible way to change that.

We should be careful not to assume that devolution will immediately transform England’s economic prospects. New institutions take years to bed in properly, and as I said in the first piece in this series, it is anyway better to assume that supply side reforms to the economy won’t bring benefits until after you’ve left office. But getting England’s state – and its local transport, planning and public services – fit for a modern economy is probably a prerequisite for increasing the country’s growth rate in the long term.

The state we’re in…

I’m not going to rehearse the disparities in living standards between different parts of England – the huge gaps in income, wealth, healthy life expectancy, educational outcomes and so on between different parts of the country – here. But I am going to quickly rehearse the current structure of local government in England. Exciting stuff!

Local government in England is a patchwork quilt of institutions and geographies. There are at least four different types of local authority in England, and they sit messily alongside each other.

In most counties, local government has a two-tier structure, with County Councils covering chunky items like roads and social care, while much smaller District Councils cover things like parks, bins and, most crucially, planning.

There are also Unitary Councils, which normally cover cities, or parts of cities. They do all the functions of a council in one.

In the major cities – the Londons, Greater Manchesters and so on – you normally have a number of unitary local authorities. Most big cities then have a thing called a Combined Authority (except in London, different as ever) which sits above the local authorities, but works closely with them*. Many Combined Authorities have a Mayor, though some do not.

But for smaller cities, you typically get a unitary authority on its own, next to a county (or something else). Think of Plymouth and Torbay, two unitary authorities within two-tier Devon, or Blackpool and Blackburn doing the same within Lancashire.

And then, also, some counties have been turned into unitary councils. Either the whole county as one authority (Cornwall, Herefordshire), the county split into two authorities (Cheshires East and West) or, in Berkshire’s case, six separate unitary authorities. Confused yet?

Just to add to the fun, other bits of government have their own geographic structures, and they don’t overlap much either. Want to connect your police force to your local authorities? Sorry, they don’t line up. How about health, those Clinical Commissioning Groups? Different geography again. Everywhere you look in government, the map of England looks slightly different. And that makes local service delivery somewhat tricky.

We also can’t talk about local government without mentioning funding and resources. Local government has been emaciated by funding cuts over the last 12 years, having received far bigger funding cuts than any other part of government. Many local authorities are now in outright financial crisis, but even those that aren’t have had to severely curtail services. This is important, not just because local authorities are struggling to provide their current services, but because they just generally lack capacity – to form new legal structures, to make new strategic plans, to plan for taking on new powers. Local government needs rebuilding more than it needs reforming.

Getting the geography and institutions right

Devolving power is not the same as willing it. In many ways, devolution is more complex than most other policy areas; it is about changing the way you do things rather than changing what you do. It’s not just a matter of agreeing policy and passing legislation. You need to design and build the institutions you’re devolving power to, and make sure they are actually ready to exercise that power. You need to take power out of government departments, and work out what role those departments need to play once those powers are spread around the country (devolution still requires support from the centre).

A crucial pre-requisite for real devolution is that you have somebody to devolve powers and funding to. At present, only a handful of places in England – mainly those with mayoral combined authorities – have devolution-ready institutions. If you want to devolution in England to be sustained, and to reach every part of the country, that needs to change. This should be the next government’s first priority on devolution in England.

In my view, the best solution is to form Combined Authorities (or something equivalent) covering the whole of England. Combined Authorities are a surprisingly good option for filling the gaps. They sit alongside existing local authorities – indeed, the local authorities become key members of the Combined Authority – so you don’t need to abolish or reform any local authorities. They are quite flexible – they can have a mayor or no mayor, and can have slightly different governance models. They go with the grain of recent reforms**, and wouldn’t require major disruption or new legislation. And they are real institutions, that can spend money, hold powers and get serious things done.

My suggestion would be to have around 50 Combined Authorities covering England. These would have an average population of about 1 million (though probably varying between about 400,000 and nearly 3 million). Existing Combined Authorities would remain, but have the chance to change borders if they want to (looking at you, North Somerset). I expect the resulting authorities would have fairly recognisable place names, such as Devon, Cumbria, Swindon and Wiltshire and so on. Mayors would be optional – and probably not encouraged in rural areas, though might be worth incentivising in some remaining urban areas.

Government would invite existing local authorities to make proposals to form, which gives local areas a degree of choice. So Lancashire, for example, could decide whether it preferred a one-Lancashire Combined Authority or to form two, perhaps East and West Lancashire. But there would be a deadline, there would be no option not to take part, and every area must be included one way or another. If necessary, the next government should be prepared to take matters into its own hands if local authorities cannot agree. Of course, this negotiation would also take place alongside the carrot of devolution discussions, which should help to focus minds among local authorities.

There are some powers that should be passed to a different level than Combined Authority. Regional transport probably requires regional bodies, such as Transport for the North, created by then weakened by the current government. Some powers – community ownership, parks, maybe some public services or active travel – can be passed down to much smaller levels of government. Many powers also sit best at the existing local authority level. With Combined Authorities in place alongside existing local government, you would have a basis for sending the right powers and funding to the right level.

There are some questions you might ask about this plan. Why can’t we just devolve powers to local authorities? Many of them are too small to adopt powers like transport and skills. And if you just devolve to upper tier County Councils, you leave the Districts (who have all-important control over planning) out of the process.

Why can’t we just form regional partnerships to do this? Frankly, regional partnerships are not proper institutions. They don’t have legal form, they don’t have proper bank accounts, they can’t really do stuff. Devolution requires a proper legal basis, not just goodwill.

Anyway, once you’ve got that geographic coverage in place, you have a good basis for devolution across the whole of England.

Disbursing funding or devolving power

There are two parts to devolution: funding and powers. Funding tends to be the more glamorous part, forming the centrepiece of ministerial announcements and local news stories. But while the devolution of powers is rarely understood outside a few local government specialists, powers are arguably where the real action is on devolution. Funding can easily be revoked, repurposed or subject to Whitehall controls. Powers are what give local governments freedom to make choices and long term plans without permission from central government.

Devolving funding is a relatively straightforward task, though it requires a degree of political will and cross-government discipline. Local authorities receive – and often have to spend precious time bidding for – a wide range of small funding sources from many different central government departments. The next government should look to sweep as many of these away as possible, giving local government much bigger, more flexible grants to achieve the objectives Whitehall sets for them. The easiest way to do this is to create a “single pot” as part of the next government’s first spending review. Identify all the money that is going to local government, fold it into a single fund, and allocate it as a single block to local government, with some requirements for how it can be spent. This can then be reviewed each year, with under- and over-performing authorities penalised or rewarded as necessary. The benefits of this approach for local government – more certainty, more flexibility to optimise funding - will be significant, as long as central government sticks to its course and is not tempted to resume meddling with funding.

Devolving powers is a more complex task, and not an especially glamorous one. There are many, many powers that central government holds, built up over centuries of legislation, and they need to be unpicked carefully. These powers are things like the right to enforce traffic penalties in certain situations, the right to regulate certain types of business, the right to set bus and train timetables and so on. Powers aren’t, in themselves, the kind of things politicians tend to make big, newsworthy announcements about. But powers are at the heart of real devolution – unless you cede actual, legal control of things to local government, your devolution is entirely reversible, perhaps even temporary. Over the longer term, the next government should focus more on powers, trying to gradually transfer powers from Whitehall to Town Hall, as local government slowly begins to rebuild its capability.

The holy grail of devolution, which combines funding and powers, is fiscal devolution – the ability to raise and keep taxes locally. There are many options for giving local government the ability to raise more of its own money, ranging from small measures like tourist taxes and powers to retain business rates or supplement them, to larger items such as local income, property taxes or road pricing. Gradually escalating fiscal devolution should be the long-term goal, but it comes with risks. Raising taxes locally tends to favour already more prosperous local authorities (devolved tax takes would be much higher in central London than elsewhere), and so some form of block funding distribution may be required in the transition towards fiscal devolution. The problem of different areas competing for business investment by lowering tax rates is also a potential risk. Neither of these is a good enough reason to avoid fiscal devolution, but it means a gradual, careful transition is probably wise.

What should the next government actually devolve?

Gordon Brown’s Review earmarks roughly the right areas for devolution in England, which is encouraging. Skills, employment, transport and housing are the bread and butter of devolved economic powers, while the inclusion of areas like energy and climate, childcare and innovation funding suggests a willingness to think more ambitiously. The challenge, though, is to match ambition with the right suite of detailed powers in each policy area.

Transport is always high on any devolution wishlist, and England already has a good benchmark to aim for: London-style transport powers. Devolving transport means letting local government control when and where buses and local trains will run, who provides them, what they cost and enabling passengers to pay with a common smartcard. These things require serious powers, such as bus franchising, a form of nationalisation. In theory, metro mayors can already take on bus franchising powers, but the legal risk and cost for doing so is exorbitant (taking control from private bus companies means legal action). If it is to be serious about devolving transport, the next government will need to legislate to make it much easier to adopt bus franchising and control of local rail networks. Integrated funding pots can help on transport, but the real action is in backing it up with powers.

There are other examples where the next government should be bold and give much stronger powers to local areas. On housing, for example, much stronger Compulsory Purchase powers over land could be transformative. If local areas are able to buy land from hold-out private entities more easily, they should be able to raise money from planning gain (the increase in land value when land is marked for development). This means more money to spend on infrastructure, services or anything else.

On skills, the government has to date been happy to devolve the Adult Education Budget (which funds college places for people over age 19) but has kept the much larger pot of funding for 16-18 education in the centre. If local government is to have real sway over the colleges and further education institutions in their area, there is a case for shifting the whole skills budget, not just the easier part. Alongside this, policies like apprenticeships (and the levy which funds them) should be in the mix for devolution.

The next government should also not shy away from more complex forms of public service reform. One of the greatest promises of devolution is the ability to integrate services that rely on one another. For example, the NHS depends heavily on (and is often let down by) the social care system, which is mostly run by local authorities. Improving educational or employment outcomes can reduce crime. Improving the natural environment can reduce the burden on the health system. There are plenty of other examples. Local areas can, in theory at least, join up these services in a way that silo-prone Whitehall generally cannot. The answer here is not always devolution, but the next government should actively explore opportunities for re-designing public services from a local angle. If local areas can find models that work better, there should be no sacred cows, no service too precious to devolve or localise if that is the best option.

This list could go on, but hopefully the message is clear. The next government should be brave on devolution; there is no point half-devolving policy areas. It must focus on powers, and take the seemingly unglamorous work of empowering local government seriously. It should hand over funding, and move towards fiscal devolution gradually over time. And for for any of this to work, it should create flexible but consistent institutions – in the form of Combined Authorities – across England. But perhaps most important of all, the next government will need to really believe in devolution, and resist the temptation to meddle once it is done. Changing the way the country is run will take time, patience and discipline, but if it doesn’t happen soon, the change might start to happen by itself.

Footnotes

* Historical note: many major city regions used to have single councils, known as Metropolitan Councils, covering the whole city region. These were abolished by the Thatcher government in the 1980s, as part of a wider weakening of local government during that period.

** Annoyingly, the current government has this week announced new devolution deals in Norfolk and Suffolk which go against the grain of using Combined Authorities for devolution deals. These deals are solely between government and the County Councils (creating a directly elected leader in each), and therefore exclude the District Councils, while also blending the devolved powers normally given to a metro mayor with the existing powers of a local authority leader. My sense is that the next government will need to unwind any non-standard deals such as this.